(Looking for a swallow rather than a full glass? ORANGE Squirt below.)

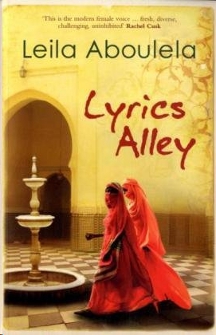

Lyrics Alley is set in 1950s Sudan, a few years before it gains independence. It’s a time of intense upheaval politically, but the focus of Leila Aboulela’s third novel is personal upheaval in these years.

Readers might guess that from the fact that the novel opens not with a map but with a short cast of characters and a family tree. And readers might guess that it’s a man’s name topping the list of principal characters: Mahmoud Abuzeid, who is described as the head of the Abuzeid family and married to two women.

Don’t worry: it’s not a long list. Leila Aboulela only requires her readers to get cozy with a handful of wives and siblings and cousins, and she gives you sufficient time to get acquainted before the plot of Lyrics Alley intensifies (and some unexpected things happen, of which you’ll hear nothing from me).

The voices are readily distinguished and stylistically vary enough to assist the reader without being so starkly disruptive as to mar the overall tone of the novel.

For instance, the voice of Nur, the poet might make this observation: “He inhaled the smells of cardamom with coffee, incense with sandalwood, cumin with cooking, luxuriated in the sounds of water being poured on the ground, a donkey braying, the birds riotous, knowing, hopeful and small; loud and fragile.” And his perspective contrasts naturally with the voice of Nabilah (as shown below), which touches on the same subject but lacks his sensory detail.

(I didn’t have any problem at all keeping the characters straight and had them in order more quickly than I ordered the wives in Lola Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives and the children in Tishani Doshi’s The Pleasure Seekers.)

Lyrics Alley opens with Soraya, a young woman in love. Readers will find it easy to connect with this quietly spirited young woman, who turns to literature for pleasure and comfort. “She read while chewing. Lorna Doone, Rebecca, Liza of Lambeth, Emma and The Woman in White….”

Soraya does not find it easy to connect with her uncle’s second wife, Nabilah, however; still, she looks to her for inspiration and wholly admires her modernity, her belief in educating women and girls, her independent and forthright spirit. (Nabilah is my favourite character and I found myself looking forward to her chapters.)

Nabilah is not entirely comfortable with the young Soraya either; in fact she is frustrated and disappointed by her in many ways. But not as frustrated and disappointed as Nabilah is with her life in Sudan which, she believes, inferior in every way to her life in Egypt. She longs to return to life with her mother and grows increasingly angry with what she views as the backward ways of Sudan.

“Nabilah surrounded herself with the sights, accents and cooking smells of Egypt, closing the door on the heat, dust and sunlight of her husband’s untamed land.”

These traditions are embodied by Mahmoud’s first wife, and much of the novel’s tension is rooted in the literal and metaphorical struggle between these women.

It manifests itself in many ways, from different patterns of relating (be it husband-wife, parent-child) to stances on social issues (female circumcision, housing arrangements) to their opposing reactions to specific situations that arise in the family.

Family is definitely at the heart of this novel. Even in his business dealings, Mahmoud places a primacy on this.

“We are a family business, Sir. We do not want outsiders to come between us,” he explains, when a potential investor queries as to why Mahmoud is approaching him rather than going elsewhere.

Nonetheless, Mahmoud’s relationship with his sons is very different from that they have with their mothers.

When he is watching Nassir and Nur, now young men, while they are sleeping, Mahmoud thinks: “His children were an extension of him and he had hopes and plans for them, which he expected them to obey, but his core, his inner depth, was independent of them.”

These are universal themes (parents’ expectations and children’s failures/successes, unions and severances, prosperity and stagnation, tradition and innovation, and independence and cooperation). But the overarching theme is change, whether it stampedes forward or dallies on the margins:

“Changes all around, but weeks, months and a whole year passing without the slightest improvement in [X’s] condition, or the faintest of progress.”

Offering another perspective on the family’s life, and their improvements and progress (or lack thereof) is Ustaz Badr. He also offers another experience of life in Sudan, one which contrasts in many ways, as he is a teacher and private tutor to two of Mahmoud’s sons.

(He was my Next Favourite character, although I’m sure the success of our relationship depends upon his being confined to the pages of a book, as our opinions on matters of religion and sex roles are certainly opposing. I chalk that up to the author’s skill at drawing me into his world despite those differences between us.)

Lyrics Alley is set in Sudan, but Leila Aboulela takes her readers across borders in such a way that we can observe differences and universals simultaneously. It’s a satisfying story overall, with each character depicted in bold strokes and a broader arc with a credible — if not completely and entirely happy — resolution that’s definitely worth reading (although, selfishly, I think I might have enjoyed a whole novel about my favourite characters even more).

ORANGE Squirt 2011: Book 16 of 20 (Leila Aboulela)

Originality Story of a Sudanese family, set in 50’s Sudan and Egypt

Readability Fairly strong, in a family-saga-ish way

Author’s voice Subtly changes to reflect different narrators

Narrative structure Head hops, but clearly and purposefully

Gaffes None spotted

Expectations Won the Caine Prize and previously nominated for Orange-ness too

Say something bookish, or just say 'hey'