If Marian Engel had not died mid-career, her name might have been as well known today as Margaret Atwood’s today. Instead her name graces an award granted to a Canadian female writer mid-career by the Writers’ Trust.

A variety of forms, a strong feminist voice, challenging female characters, a fascination with boundaries (and crossing them): Marian Engel’s works are bold and insistent.

A variety of forms, a strong feminist voice, challenging female characters, a fascination with boundaries (and crossing them): Marian Engel’s works are bold and insistent.

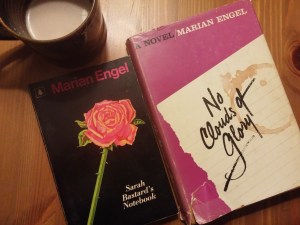

Like Sarah, in No Clouds of Glory, which was also published as Sarah Bastard’s Notebook in 1968.

These are the ruminations of a young woman who is uncomfortable with the place she seems to be expected to inhabit in society but also uncomfortable with the new ground she seems to be breaking.

“I am a lady Ph.D. One of an increasing multitude, but in my own point in time and space, a rare enough bird, the only one the [news]paper felt like rooting out that year, the only one at my college under fifty, and their series was on ‘Young Canadians’. And two weeks ago, I hadn’t yet turned thirty.”

Not only in public, as she was interviewed in “The Toronto Star”. But in private, too, she considers herself an outsider.

She travels to Yurp, but she doesn’t belong there either. (That’s Europe, in trite-speak. It took me a minute.) She inhabits a series of bed-sits; it’s not real living, she says.

Even so, Sarah is travelling the same path that writers like Mordecai Richler and Mavis Gallant, Brian Moore and Margaret Laurence travelled, moving through places overseas, gathering experiences unlike her own. which seem to end up only echoes of familar experience anyway. It was once adventurous, but now it’s trite; going to Europe seems like taking a pony ride now.

Times are a-changing. Which means that they are still a lot the same and some different. One scene can contain a landlady who insists that Sarah’s companion book a night in the lodgings across the street. Another scene contains a woman’s decision to abort an unplanned pregnancy.

Nonetheless, Sarah insists upon her independence. Her determination to make a life beyond family. Despite her friend (and sometimes lover) Joe’s belief otherwise. If she’s not lonely, he suggests she might be “half Lesbian”. But she’s simply looking for something else.

Nonetheless, Sarah insists upon her independence. Her determination to make a life beyond family. Despite her friend (and sometimes lover) Joe’s belief otherwise. If she’s not lonely, he suggests she might be “half Lesbian”. But she’s simply looking for something else.

“If I could be the man, bring the bone home myself, not raise babies – maybe. But there’s too much to do and see. I’ve been years in prison, Joe.”

Sarah’s sister, Leah, exemplifies an idea of womanhood, of femininity, which Sarah can’t seem to disdain. Even though part of her does seem to hold it in contempt, she still longs for the acceptability that accompanies more traditional choices.

“She [Leah, her sister] had, in fact, quietly from the beginning of her life, and tidily, rejected the significance of everything I found bearable in our existence. She squatted in corners telling herself stories, to be far away from us. No snugness of armpits for her, no glorying in repellent love. I ooze, booze, stink, feel human rather than feminine, live in a welter of Kleenex and newspapers, cats, clay pots, pictures of people, dust. She is cool as a cat, aware, and apart.”

For much of the novel, Sarah is in motion. The prose doesn’t have a conventional arc. Readers kind of sink into it and wallow a little, rather than move through a series of events or realizations. “I was always in debt to airways and abortionists. I was carrying a more and more terrible guilt.”

It’s also uncomfortable reading, at times. Partly because either Sarah isn’t comfortable in her own skin or because she so keenly feels that others believe she should not be comfortable in that skin. “‘Sarah has changed,’ people said, smirking knowledgeably about Yurp.”

She doesn’t feel like she fits. “‘You have me confused with the peace marchers. I don’t belong to any generation.'”

And the world of academia – at home – isn’t any more satisfying than her voyages abroad. She is critical of the life and as much as she feels herself a part of it, she feels separate from it too. Separate and powerless.

“The edges are dulled – news takes a long time to come, and ceases to seem important. It’s something in the air, and perhaps a fundamental disbelief in temporal values. The only literary thing which really interests me is what is happening to literature now, why people write what. But we keep ourselves isolated from – the passion of making literature – from the passion of discovery. That’s why we don’t produce anything.”

In short, Sarah is longing for something more. That doesn’t seem so far removed from now.

The 1968 club is hosted by Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Stuck in a Book, during October 30 and November 5, a reading week which focusses on books from a particular year, reading and reviewing and sharing ideas about the kind of works published then.

It was exciting to read a review of a Marian Engel novel! I have wonderful memories of reading The Honeyman Festival and Monodromos – I think she would be a wonderful author for a smaller press to reprint. Sarah Bastard’s Notebook is the next of her books on my to-read list!

[…] Kaggsy and Simon: Robertson Davies’ Tempest-Tost (1951) #1968Club Hosted by Kaggsy and Simon: No Clouds of Glory Non-Fiction November Hosted by Katie, Lory, Julie and Kim: […]

I’m not familiar with this author but I really like what you’ve written here about her writing and of course if she’s compared to Margaret Atwood then that certainly catches my attention!

Thanks, Iliana: she’s worthy of note, although I’m sure it would be a challenge to find an early work like this one in the U.S. these days.

Talking about how she and other well-known Canadian authors traveled to Europe in those days, and it was a much bigger deal then, makes me think about LMM travelling overseas for her honeymoon. I was always in awe of that. She felt so PEI-ish to me, it was hard to imagine her over there. The thought of it in association with the others you mention feels kind of lonely. Like they were searching for something they felt was missing from their lives.

Anyway, I’ve been meaning to read Bear for so long – and now I want to read more than just Bear. 🙂

That’s something that always fascinated me as well. It seemed impossible. And, yet, wasn’t it not much afterwards that Mazo de la Roche was not only writing and making scads of money like Montgomery was, but she ended up living in England for a time (in a most magnificent mansion), before returning to Canada. But, then again, even though I think there were only about a dozen years separating those experiences, they were probably very important years, in terms of social and economic changes. I’ve also wanted to go back and read Lunatic Villas actually and now that I see Joanna was written in a series of small pieces about marriage (hint, hint) for radio (they look like blog posts!) I am curious about that too.

Lunatic Villas and Joanne both sound great! Sigh.

Oh dear… I just put her “Life in Letters” on hold. Lunatic Villas might be more appropriate right now. 🙂

That’s the one I’m thinking of snagging as well; I really enjoyed the collection of letters between Engel and Hugh MacLennan (also edited by Verduyn). It’s at a branch nearby, but, fortunately, not one of the nearest, so that I can make myself wait just a little longer (and finish with the prizelists first – sigh).

The trials and tribulations of book lovers… 🙂

[…] No Clouds of Glory by Marian Engel Buried in Print […]

Never heard of her, but apt inclusion since I’ve just been in Toronto – and thanks for contributing. The change of title intrigues me!

She only mentions a couple of specific places in the city, so there are definitely more Toronto-soaked reads you might like. I’m curious why you travelled so far to come here and whether you were able to see any of the good bookshops (second-hand in particular) after having made the trip. Yes, the title change interests me too, but since both of my copies date to the publication, I will have to find another source for an explanation of it.

Marian Engel is not an author I’m familiar with either, but it seems that she deserves to be better known. This sounds interesting, even if it’s not a comfortable read.

Considering she was mid-career when she died, she left behind quite a substantial body of work. There is enough character in this one to save us from feeling at-odds throughout!

I am intrigued – a comparison to Margaret Atwood and the quotations you shared are excellent!

I’m glad I pigued your interest: she is an intriuging writer!

As a can-lit lover I’m embarassed to say I haven’t read any Marian Engel, although I mean too, sooner rather than later, she seems like the kind of author I need to have in my life!

We can’t read everything, can we! The easiest one to find is, of course, Bear. Which I absolutely adore. But it’s not for everyone. And you might actually want to read the introduction to that one first, depending on what cover illustration you happen upon!

Thank you for sharing some CanLit with us for 1968 – that’s part of the joy of these clubs, discovering new authors. And Engel certainly sounds worth reading!

Thanks for the encouragement to pick it up and for hosting the event. I was determined to choose a Canadian writer, and the other was reaching back into the past (the Depression years) so this seemed a more 60s-ish story.

I’ve not come across Marian Engel before but this sounds interesting. Might it be a little autobiographical?

It’s been years since I read her diaries and notebooks from the library, but at least some of it must have been drawn from her personal experience.