The FOLD (The Festival of Literary Diversity) is an annual event, in Brampton (Ontario, Canada) dedicated to telling more stories, to having audiences connect with a wider variety of storytellers. You can check out their lineup of terrific writers and storytellers who were a part of the debut festival in May this year, here.

The FOLD (The Festival of Literary Diversity) is an annual event, in Brampton (Ontario, Canada) dedicated to telling more stories, to having audiences connect with a wider variety of storytellers. You can check out their lineup of terrific writers and storytellers who were a part of the debut festival in May this year, here.

Earlier in 2016, they posted a reading challenge, which I printed and dutifully began to read towards. (I’ve misplaced the link: sorry!)

Earlier in 2016, they posted a reading challenge, which I printed and dutifully began to read towards. (I’ve misplaced the link: sorry!)

- A book you’ve had for more than a year.

- A book outside of your ‘favourite genre’.

- A book you buy at an indie bookstore.

- A book by a person of a faith.

- A book by an aboriginal author.

- A book by a Canadian LGBTQ author.

- A book by a Canadian person of colour.

- A book by a FOLD 2016 author.

I’ve already discussed the first and last categories, Ernest J. Gaines’ A Gathering of Old Men (1983) and Farzana Doctor’s All Inclusive (2015), and the fourth, André Alexis’ Pastoral.

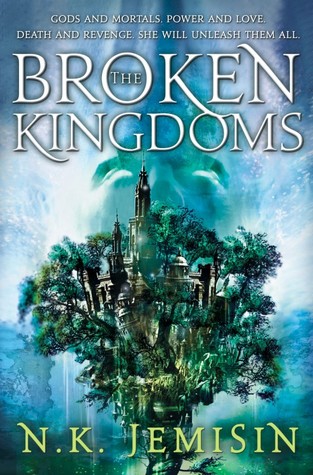

Today: a book outside of my favourite genre, N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Kingdoms (2010) which is the second in her Inheritance fantasy cycle, and a book by a Canadian person of colour, David Chariandy’s Soucouyant (2007).

At first, Soucouyant appears to have a fantastical side too: “What do you do with a person who one day empties her mind into the sky?” (This is particularly the case when reading N.K. Jemisin’s series, in which Sky is an actual place.)

But, in fact, there is an unfortunately banal explanation. “The word is old and has been used in medical contexts for over two thousand years to describe many types of unusual or incomprehensible behavior. Today, the word is most often connected with illnesses associated with aging, so much so that the terms ‘early onset’ and ‘presenile’ are applied when cases arise in people barely forty years old.”

Everyone knows the word. Everyone knows what the younger son is facing, after he returns home to care for his mother. But of course this is not the whole story. “They does always tell the biggest stories in book.”

Delving into a fresher understanding of his parents’ lives, he probes into darkened corners. “There were mildewed explanations for why they shouldn’t ever get along. An African and South Asian, both born in the Caribbean and the descendants of slaves and indentured workers, they had each been raised to believe that only the only had ruined the great fortune that they should have enjoyed in the New World.”

Soucouyant is characterized by a watery landscape on- and off-the-page. Talk of mildew laps against more concrete imagery.

“For a long time, I never understood what ever could possess my parents to live here. This lonely cul-de-sac in the midst of a good neighbourhood,’ this difficult place that none of our neighbours would ever have settled for. It could have been the great lake, of course. That mirage of steel and pastels stretching out to the very horizon of the world, that inland sea inspiring all sorts of reckless imaginings.”

Talk of possession, too. “Do you know what it’s like to be around someone who’s eternally sad? It drains you. It sucks your life.” (In the quote above, as well.)

Talk of possession, too. “Do you know what it’s like to be around someone who’s eternally sad? It drains you. It sucks your life.” (In the quote above, as well.)

This is a short novel, just as his mother’s is a short life. “Man can’t take care of you. Friends, husbands, sons, they all the same. They does leave you.”

It is the story of those who have been left. Yes, a sad and draining story. But one beautifully told.

N.K, Jemisin’s novel The Broken Kingdoms is also relentlessly sad, but Oree’s character is dynamic and tenacious.

“My parents named me Oree. Like the cry of the south-eastern weeper-bird. Have you heard it? It seems to sob as it calls, ore, gasp, ore, gasp. Most Maroneh girls are named for such sorrowful things. It oculd be worse; the boys are named for vengeance. Depressing, isn’t it? That sort of thing is why I left.”

Although the second in the Inheritance Trilogy, readers could approach The Broken Kingdoms as a standalone. The events of the first volume, The Ten Thousand Kingdoms unfolded a long time ago, and they are recounted succinctly, which serves as a solid refresher/introduction.

N.K. Jemisin deliberately situates readers in time and space, primarily through their relationship with Oree, which is key to this novel.

“These days, our world has two great continents, but once there were three: High North, Senm, and the Maroland. Maro was the smallest of the three but was also the most magnificent, with trees that stretched a thousand feet into the air, flowers and birds found nowhere else, and waterfalls so huge that it was said you could feel their spray on the other side of the world.

The hundred clans of my people – called just ‘Maro’ then, not ‘Maroneh’ – were plentiful and powerful.”

In fact, Oree’s understanding of events undergoes a dramatic shift as The Broken Kingdoms unfolds. So readers who began at the beginning will be more profoundly affected by her realization/discovery, but her awe and surprise is enough for readers who did not know (or had forgotten) an alternative version.

Ultimately, the novel is as much about patterns of behavior in our own time (and historically) and space. The trials which Oree faces are ripped from the headlines in readers’ experiences.

“How many nations and races have the Arameri wipedout of existence?’ I demanded. ‘How many heretics have been executed, how many families slaughtered? How many poor people have been beaten to death by Order-Keepers for the crime of not knowing our place?'”

The novel’s pace is relentless and after a short grounding in Oree’s experience, there is a single death and then there are many. The Broken Kingdoms, unlike readers’ reality, has a resolution. Oree’s tale needs telling and a tale-telling needs listeners.

“Then listen. That’s the most important thing any historian can do.”

Both The Broken Kingdoms and Soucouyant endeavour to tell the stories of those whose versions are often shelved in the appendices, laid out in the cul de sacs on a crumbling lakeshore.

Compelling stories.

Are there books in your stacks which would fit any of these categories?

[…] set further north of the bluffs, David Chariandry’s follow-up to his debut Soucouyant is every bit as family-soaked, its losses and sorrows cast against a remarkable and enduring […]

[…] already discussed the following: Ernest J. Gaines’ A Gathering of Old Men (1983); N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Kingdoms (2010); André Alexis’ Pastoral; David Chariandy’s Soucouyant (2007); and Farzana […]

I read Jemisin’s The Broken Earth series first because it was her most recent, but do plan to read her Inheritance trilogy eventually. I think she’s brilliant and want to read all her work.

FOLD sounds fantastic. I’d love to have such a festival near me! Lawrence Hill is going to be there :O and a few other faces I recognize.

Please keep reviewing books that fit the 2016 challenge. It’s such a simple yet effective way to read widely and add variety to your reading.

When I started reading the series, it was her most recent. Yeah, I’m a little behind. But that’s okay, because I love knowing that there are so many more to enjoy now. So pleased to hear that you enjoyed the Broken Earth series so much: it sounds fantastic!

I love fantasy and books not quite realistic so my shelves are full of them. Been meaning to read Jemisin for ages. Must get around to that! Do you think you will be exploring fantasy more? Has venturing outside your favorite genre found you some new favorites?

It’s not that I deliberately avoid the genre, it’s just that I haven’t read it with any dedication for more than 15 years now, so it doesn’t feel like familiar territory anymore. But every time I dip my toe in, I wonder why I don’t take a more deliberate plunge: so much great material there. Are there particular titles/authors you would recommend which are recent offerings (and, by recent, I guess I mean from the past decade or so *chuckles*)?